The Sandrigo – Monte Corno race was the last Italian competition of the year for all of us. Perhaps it was the most adventurous weekend, even though nothing extraordinary happened.

Originally, we were set to compete in four races from August 24 to September 1. I had been waiting since July 18 to take the start line. It always seemed like I was traveling, but just a day before departure, the news would come that I’d have to wait for the next opportunity. It turned out this time that I wasn’t included in the lineup, but I kept training because another race was coming up.

And train I did—harder than ever. Just two days before the August 23 departure, my dad received a call saying there were logistical issues with the team. Some riders were planning to continue to an international race after the September 1 event, and they would be taking the minibus. So it was suggested that I compete in the races on August 31 and September 1, and my parents could take me there and back. This complicated our lives significantly. Everything had already been prepared for the weekend of the 23rd to 25th. My classmates had organized a birthday party for me, which I canceled solely for this race—one I ultimately didn’t attend. I’m always ready to set aside everything for the sport, but now I had to throw it all away for nothing. That hurt.

Yes, this is part of high-level sports, and it’s something you have to learn to accept without complaint. Of course, faster communication would have spared us a lot of discomfort, but let’s turn the page.

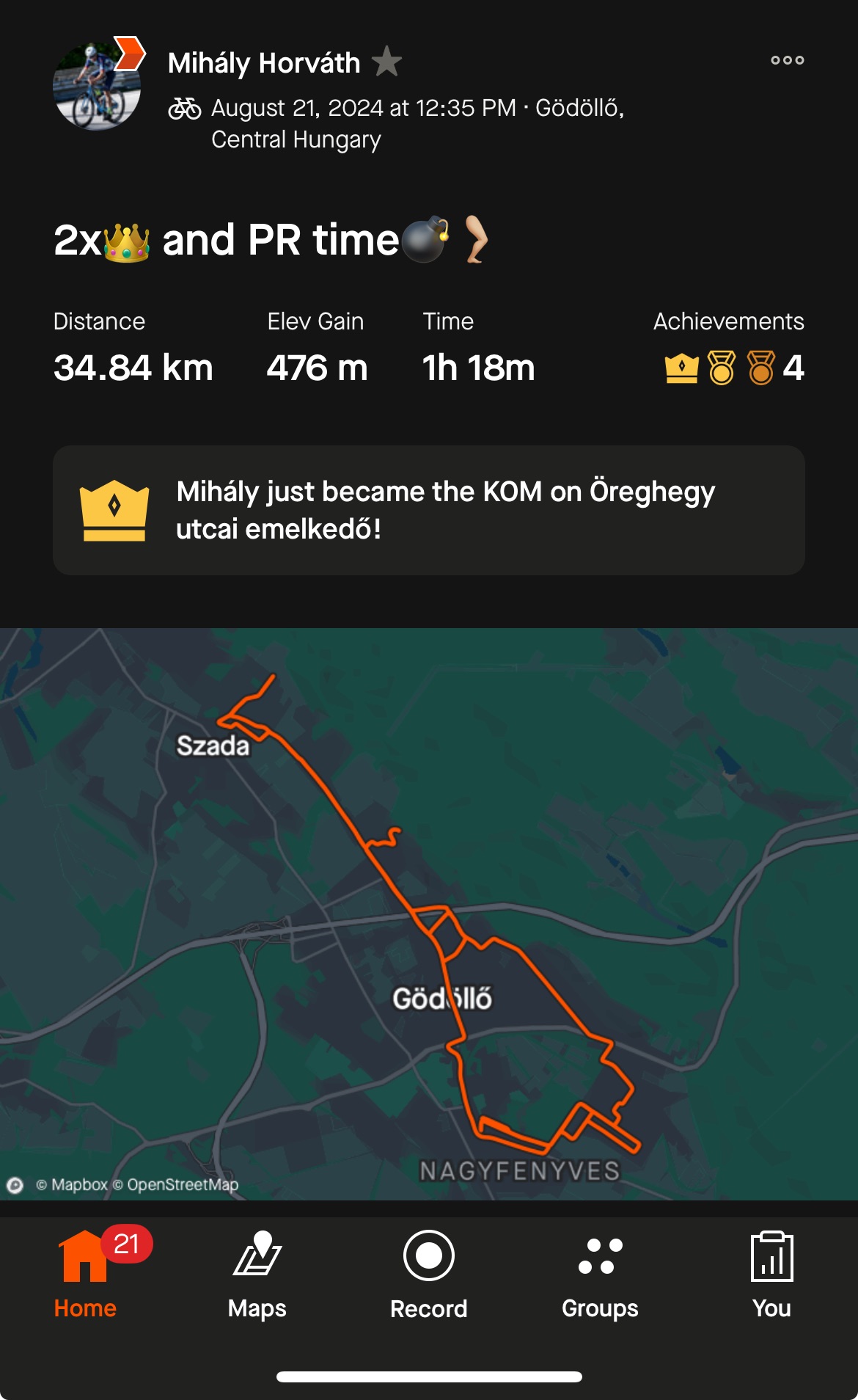

That day, I went out to train, tackled two KOMs, and improved my personal best wattage by 30 seconds. That was the only right way to respond to so much bad news.

In the meantime, it turned out there would only be one race instead of two. So, we set off a day later and arrived on August 31, Saturday. Finally, I got to meet up with my teammates who had stayed behind after the previous race and would be lining up with me the next day.

No one from MBH was present, and by the evening, we still didn’t know who would provide us with water bottles for the race. We certainly didn’t want to relive the experience from stage 2 of the Giro del Veneto, where we only got one bottle in sweltering heat, leaving everyone struggling. With Montecorona‘s team, Gibbo‘s group, also competing, there was hope they could help with hydration, but we had no information about that. There wasn’t even a spare bike available in case of any technical issues. We hoped everything would come together in the end, but we went to bed knowing only that there was a race the next day.

The race was set to start at 1:00 PM. Forty minutes before the race, we found out that Gibbo and the Montecorona staff would be helping out, with Gibbo driving the MBH team bus and providing hydration every 4 kilometers after the criterium stage. It was a great plan, but we really only heard about it at the last minute, during which we were spinning all sorts of concerns.

Communication was complicated since we didn’t speak Italian yet, and Gibbo didn’t speak English. However, by the end, everything fell into place.

The race is 98 kilometers long with approximately 1000 meters of elevation gain. It consists of a criterium stage featuring 14 laps of 4.3 kilometers each through the city, practically at zero elevation, making it quite a grind. After a roughly 10-kilometer transition, the course then includes an average 4% incline over 25 kilometers, which isn’t always 4%—sometimes it’s less, but other times it can be significantly more.

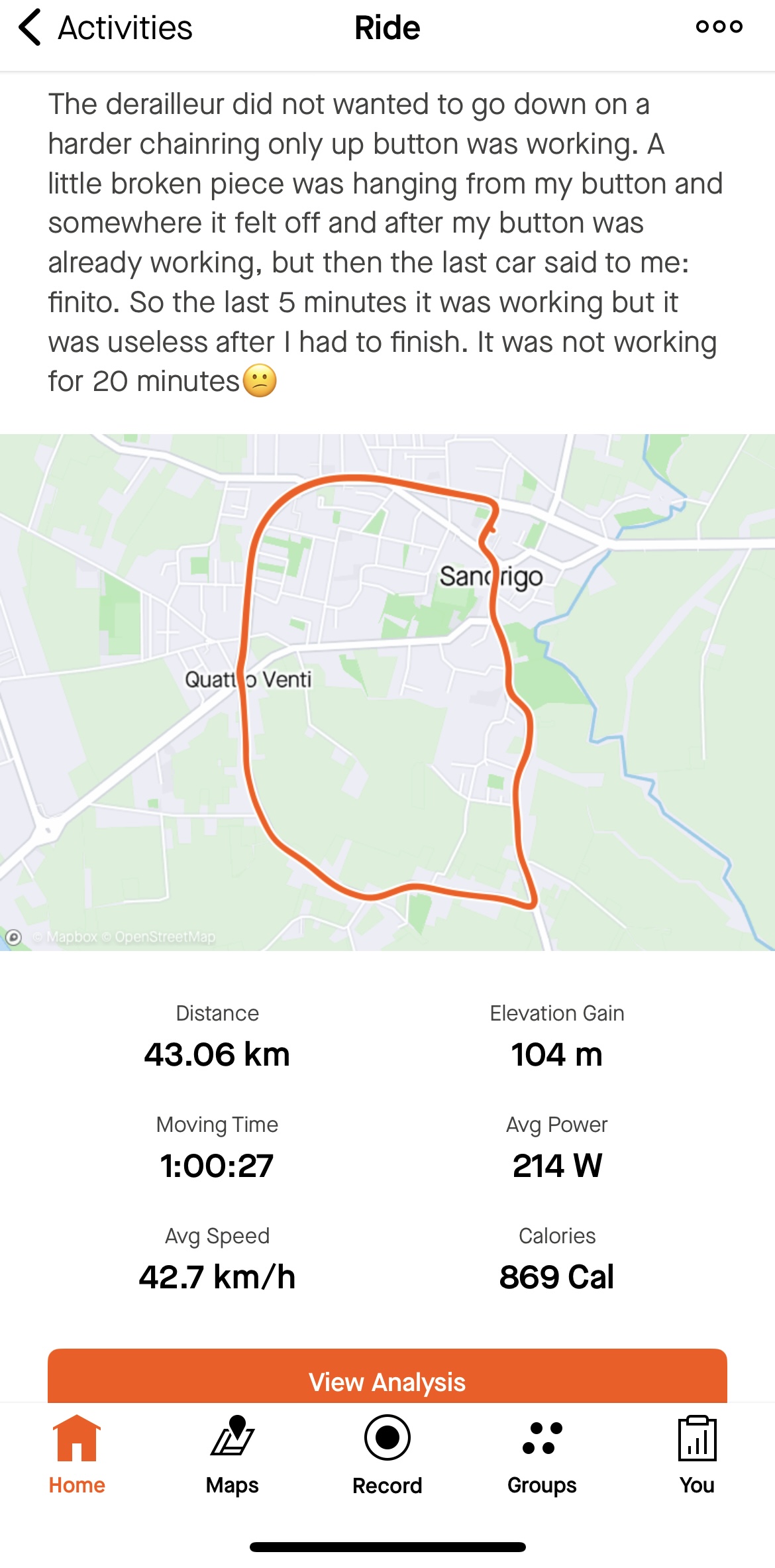

On the 35th kilometer of the race, my rear derailleur gave out. At one point on the course, I shifted down, but from that moment on, it got stuck on the big chainring and wouldn’t respond to the downshift button. It would shift up, but not down.

I noticed a sharp piece of plastic hanging from under the derailleur switch. While trying to stay with the bunch at a cadence of 140, I was struggling to pry this plastic piece loose. I had no choice since we didn’t have a spare bike available. Gibbo saw what the problem was but couldn’t help. After 20 minutes of fiddling with the derailleur lever, something finally happened, and it seemed the situation was resolved because as soon as the plastic piece stopped obstructing the shift button, I was able to change gears again.

But by the time I got to that point, 20 minutes had passed, and I had fallen so far behind the group that after five minutes of catching up at a decent speed, the broom wagon called it ‘finito.’ This marked the seventh race day that went down the drain due to derailleur issues.

Gibbo noticed how long I had been struggling, and when the broom wagon came by, he stopped and picked me up.

In sports, it’s tough to wait a month for a race only to pull out because of a mechanical failure before you even break a sweat. But I was starting to think of Fortuna as a particularly useless, cheap woman.

In the end, the broom wagon took everyone out, but Bálint managed to finish, coming in the top 20, which is a great result.